Transportation projects must prioritize public health over industry wealth, residents and advocates say

Historically, road and freeway projects have hurt communities of color in the Inland Empire. Environmental justice advocates want to change the course of that history

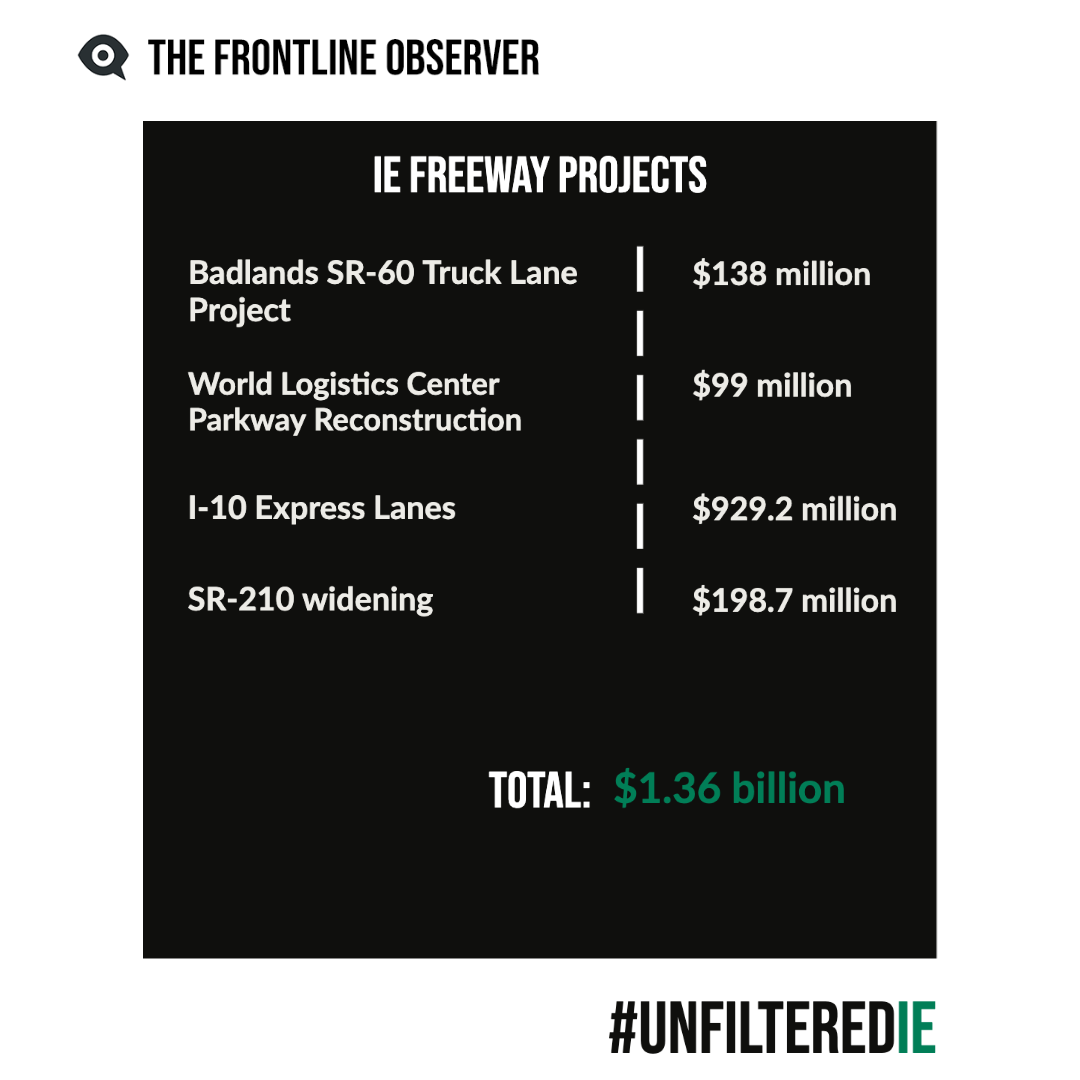

In the last 10 years, local and state transportation agencies have earmarked over a billion dollars to rebuild freeways to help ease traffic congestion and enhance the movement of goods tied to e-commerce and warehousing — the region’s largest industrial sectors.

In Riverside County, the anticipated construction and opening of the 43 million square foot World Logistics Center in Moreno Valley and continued development of large warehouses in communities near the San Gorgonio Pass and the Coachella Valley desert has resulted in substantial changes to State Route 60 near the Badlands mountain range. An ascending truck route going east and a descending truck route going west were added to the freeway to reduce truck congestion and improve traffic safety in that area. Meanwhile, Caltrans and the City of Moreno Valley are preparing for the construction of new on and off ramps, as well as overcrossing and turning lanes to the World Logistics Center Parkway exit on State Route 60.

In San Bernardino County, Interstate 10 is undergoing improvements to add express lanes from Montclair to Redlands in several phases and the 210 Freeway near the San Bernardino International Airport will see additional lanes added to both the east and west portions. Combined, about $1.4 billion in local, state and federal funds will be used for these regional highway improvement projects.

Transportation agencies and local elected officials claim such plans and projects are helping improve both mobility and quality of life for the millions of people who travel across the Inland Empire.

“We have to consider geographically where we are. We are in a county immediately adjacent to the largest centers in Southern California in Los Angeles and Orange County and near the largest ports in the world,” said Tim Watkins, spokesperson for the San Bernardino County Transportation Authority (SBCTA). “We often have a saying, ‘The ports might be the link to China. But San Bernardino County is the gateway to the rest of the country.’”

Meanwhile, residents and environmental justice advocates say that freeways and other large transportation corridors are solely meant to serve the logistics industry.

“These transportation arteries that serve the global supply chain aren't for our community,” says Hector De Leon, 21, a long-time Moreno Valley resident and environmental justice advocate. “They are pathways that help fill the pockets of logistics companies.”

De Leon is part of a community effort to ensure local agencies applying for these federal funds consider a more sustainable balance between infrastructure and community health.

The Inland Empire consistently ranks as one of the regions with the worst air quality in the nation. Since 2003, the South Coast Air Basin that includes Riverside and San Bernardino counties has had 16 years where it exceeded the national standard for ozone for over 100 days. Redlands and San Bernardino, where the warehousing and railyard industries are particularly dense, experienced 141 and 130 bad smog days in 2020 respectively.

Residents and environmental advocates point to the current urban sprawl associated with the warehouse boom as the main culprit. Area freeways and large thoroughfares provide important transportation infrastructure to Amazon, FedEx, UPS and large retail corporations moving thousands of retail products, food, liquids, vehicles, chemical liquids and gasses daily through trucks and trains. They are also a large contributor to carbon emissions fueling climate change.

By walking on the 16th Street overpass of Interstate 215 in San Bernardino, one can see the row of lanes surrounded by large walls with artistic patterns of citrus, arrowheads, mountains and trains that portray the Inland Empire’s history. It is this much celebrated urban sprawl that has helped contribute to generations of health and economic issues for this part of the city.

Inland urban sprawl has historically come at the expense of communities of color

Like many U.S. cities during the post-World War II era, urban sprawl and industrialization changed the economic and cultural landscape of San Bernardino. The construction of U.S. Highway 395 (later designated Interstate 215) led to the decline of the Mexican business community on the city’s west side. Mt. Vernon Avenue — once the city’s commercial and business corridor along historic Route 66 — became desolate in the years and decades following the freeway’s opening in October 1959.

A survey done by real estate development company Dukes, Dukes and Associates Inc. in 1980 — 21 years after the completion of Highway 395 — claimed the Mount Vernon business district area was “blighted” and “in a rapid cycle of physical decay.” Similarly, the San Bernardino Valley Redevelopment Agency would classify at least one-third of west side housing as substandard. By 1975, about one-third of residents on the west side were on public assistance, according to Census data.

Discriminatory planning decisions influenced by white business interests resulted in unusual freeway designs that led to exclusive left offramp exits that diverted traffic and commercial activity to the downtown area, explains Brown University History Professor and longtime San Bernardino resident Dr. Mark Ocegueda. By reading through minutes and recorded notes of California State Highway Commission meetings, Ocegueda learned that the public input process heavily favored white residents and failed to adequately engage Black or Mexican residents.

“There’s scholars and organizers that speak about this ‘slow violence’ that is associated with the supply chain. I think this situation falls along that line of thinking,” said Ocegueda. “Because it took about two decades for those effects to be felt.”

Scholars characterize the warehouse and logistics industry as a ‘slow violence of the supply chain’ because the health and economic impacts that low-income people and communities of color feel are not direct, but gradual. Sometimes these impacts occur over a span of generations and can even be genetic.

Raul Raya, 80, owns the historic Ybarra’s Market that sits on Spruce and I Streets right across the freeway and BNSF Railway’s train tracks. His store is barely visible when driving on the freeway or on the 5th Street west off-ramp exit.

Raya says he’s lived on the west side since his migration to San Bernardino from Mexico at six years old. Our interview setup was indicative of Ybarra Market’s decline. We sat between some empty meat counters and store shelves stocked with canned goods and other non-perishable items. “There’s a small house here in the back,” Raya shared. “That’s where we were raised.” The sounds of a train’s wheels can be heard turning nearby.

He spoke of the store’s diminished influence in the years after the freeway was built — how they slowly lost many of their customers to bigger retail grocery stores. Aside from those who live on the same street or within a mile radius of the store, Raya believes many in the city don’t even know the store exists. Nonetheless, he and his predecessor — Pascuala Ybarra — learned to adapt over the years.

“We’re still not closed yet,” he said. “We’re still open 7 days a week.”

Securing funding for freeway expansion and improvement projects

From 2007 to 2012, the San Bernardino Association of Governments (now known as SBCTA) worked with Caltrans to renovate and expand I-215 into a 10-lane freeway and adding off ramps on each side, eliminating the controversial fast-lane left off ramp exits. In total, $647 million in local, state and federal funds were leveraged to make the improvements to the highway.

A big part of that funding came from Measure I — a local half cent sales tax initiative that was initially approved by San Bernardino County voters in 1989 and again in 2004. The first phase of Measure I funded transportation improvement projects from 1990 to 2010 and the second phase is funding projects from 2010 to 2040.

According to Watkins, Measure I has resonated with voters because it has helped identify projects that would benefit the County at-large.

“[SBCTA] delivered on our commitment to voters,” he said. “So when the Measure came back to the voters, it was overwhelmingly approved because we honored our promises.’

Watkins also says that Measure I is a tool that can be used to pursue state and federal grant opportunities. According to SBCTA’s website, the agency is required to use a proportional share of state and federal funds to support projects countywide.

“It allows us to leverage additional resources for the county’s benefit,” he said.

Earlier this year, the California Inland Empire Caucus asked Governor Gavin Newsom for $2.2 billion of budget surplus funding for transportation improvements, including $875 million for five projects in Riverside County.

Historically, agencies like Caltrans and the Federal Highway Administration have reacted to large financial investments by building new freeways or expanding existing ones, says Cal Poly University Assistant Professor of Transportation Dr. Shams Tanvir.

Tanvir explained how agencies in the Greater Los Angeles area have created a “perpetual cycle” in which drivers and freight suppliers are attracted to use roads and highways, which ultimately fails to address their intended purpose of reducing traffic congestion. He says this is an example of “Induced Demand.” Expanded lanes result in more people choosing to drive on freeways thus increasing congestion, research shows.

“There are people who cannot afford to live within one or two hours within their workplace,” he said. “So they are choosing to live in communities that are farther and farther out of the Los Angeles and Orange County metropolitan area. The more distance you have to travel, the more the need to expand your highway system. It’s not a one to one relationship. It’s dependent on the movement of people in one particular area.”

The pursuit for more sustainable transportation

The other side of I-215, which both Raya and Oceguera assert was once the affluent side of San Bernardino, now faces increased problems due to damaged roads, traffic congestion and diesel pollution from trucks traversing 5th and Baseline Streets, as well as Highland Avenue.

On a recent Friday morning, there were at least four heavy-duty diesel trucks driving down Baseline toward I-215. Later in the day, there were two trucks parked near an abandoned Smart & Final store between D Street and Arrowhead Avenue with their engines idling.

Residents Jose Avalos and Ma Carmen Gonzalez are neighbors that live about half a mile east of the freeway on D Street. They both became engaged with local environmental justice and community groups after seeing the continued influx of freight activity in their neighborhood.

“There’s a lot of blight, no trees, essentially no effort by the city to try to alleviate pollution and quality of life concerns,” said Avalos. “Apart from diesel pollution, our roads continue to be damaged and filled with potholes. And vacant lots are now serving as parking stations for these trucks.”

Gonzalez believes most people are left out on freeway and transportation infrastructure projects. She points to an example of a recent decision by BNSF to extend a rail track on the westside with minimal public input. A lack of real time Spanish translation during community meetings and minimal information released about the project hindered the community’s ability to have any influence on the outcome, Gonzalez says.

“It’s not fair that they’re trampling our community’s rights, over the rights of people who are Black, Latino and non-English speakers,” she said.

Similarly, De Leon explained that the general sentiment among his neighbors in Moreno Valley is that warehouse development and the increased number of trucks that pass by their neighborhood near Rancho Verde High School is causing pessimism.

“The only time people see improvements to the streets is when they want to bring in a new warehouse development,” said De Leon. “As a result, many people are choosing to leave. I am even contemplating it.”

De Leon, Avalos and Gonzalez believe local, state and federal transportation agencies should provide more information about freeway and transportation projects. “I hear more from our local groups about these issues than I do from agencies,” says De Leon. “There’s not a whole lot of planning or conversation when it comes to addressing the lack of strong public transportation in our area, and that’s another big issue.”

According to Caltrans, staff utilizes ‘Foundation Principles’ to address community concerns related to the environment, traffic, project cost and completion dates and safety. In 2020, the agency implemented Senate Bill 743, which was approved by the state legislature to improve how to analyze impacts from transportation and other industrial projects.

“Health concerns related to environmental impacts, air quality, and active transportation options are evaluated in all projects and required to be addressed in the environmental phase,” said Caltrans chief spokesperson Emily Leinen in a prepared statement.

Additionally, Leinen explained the bill helped the agency shift from a level of service analysis to vehicle miles traveled analysis. The former approach compelled communities to expand highways, measured how fast cars traveled on roads and encouraged driving. The latter approach measures the distance in which vehicles travel and attempts to avoid highway expansions, according to information on Caltrans’ website.

Tim Byrne, SBCTA’s Director of Toll Operations, says the agency’s planning group evaluates vehicles miles traveled and sees that approach as the criteria to determine if projects have significant traffic and environmental impacts. Recently, there’s been discussions on how to reduce vehicle miles traveled by encouraging ridesharing programs, Byrne explained.

“We are sensitive to the [vehicles miles traveled] discussion,” said Byrne. “We understand that it may impact how we deliver projects in the future,” he said. “And we’re looking at how to best partner with the state on where to get where they want.”

Tanvir acknowledges the inroads state and federal agencies have made to consider safety and public health when it comes to freeway and road construction. “I applaud Caltrans for their recent change in focus,” he said. “But I still believe the agency can improve their tools and capabilities to execute on other ideas related to transportation infrastructure.”

Back at Ybarra’s market, Raul Raya points out at the freeway that obscures his business. Raya says any movement from local transit agencies and governments to be more community centered is fine, but as far as his life goes, it’s too little too late. He’s not as concerned about recent freeway expansions in the area because the 215 freeway’s damage on the westside was done six decades ago.

“The freeway doesn’t do any more harm than what’s already been done,” says Raya. “Whether it was racism or not, one thing is certain, and that is that leaders did not consider the west side.”

This story is part of the local environmental reporting initiative Unfiltered IE that is supported by the civic media project The Listening Post Collective and funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation.